The Chesapeake Bay, the largest and most productive estuary in the United States, is Maryland's grandest natural resource. The Bay drains a watershed of more than 64,000 square miles within which dwell more than 13 million people. Its ecosystem provides habitat for about 2700 species of plants and animals. The Bay's seemingly limitless bounty has encouraged the development of commercial activities as varied as fishing, shipbuilding, agriculture, steel-making, manufacturing and chemical production.

The intensity of this development has caused a dramatic reduction in the health of the Bay ecosystem. The major environmental problems of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries were investigated in a comprehensive study initiated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1975. The study's final research findings and recommended remedial strategies were published in September 1983. They formed the foundation for the first Chesapeake Bay Agreement by which the governments of Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia, in partnership with the federal government, agreed to develop and implement coordinated plans to improve and protect the water quality and living resources of the Bay.

The EPA study especially recognized that land use and population growth are major factors in shaping the historical decline in the living resources of the Bay. The number of people living around the bay determine the demands placed on its ecosystem and those demands are growing. Both water quality and wildlife habitat can be seriously degraded by the cumulative impact of intensified development from this increase in population. In 1984, to safeguard the Bay from the negative impacts of intense development, the Maryland General Assembly enacted the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area Protection Program, a far-reaching effort to control future land use development in the Chesapeake's watershed. The ribbon of land within 1000 feet of the tidal influence of the Bay was determined to be crucial because development in this "critical area" has direct and immediate effects on the health of the Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay Critical Area Commission was charged with devising a set of criteria which would minimize the adverse effects of human activities on water quality and natural habitats and would foster consistent, uniform and more sensitive development activity within the Critical Area. In cooperation with the Critical Area commission, local critical area management programs are administered by the 61 local governments whose jurisdiction are partially or entirely within the Critical Area.

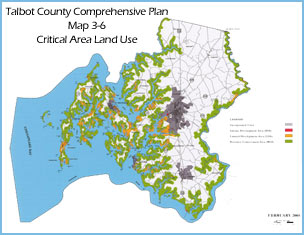

All land within the Critical Area, except for land owned by the federal government, is assigned one of three land classifications based on the predominant land use and the intensity of development at the time it was mapped. These provisions are used to ensure that land within the Critical Area is managed, used, and developed in a manner that will achieve the goals of the Critical Area Program.

Maryland’s Critical Area Program is unique not only because of the significant resources that it is designed to protect, but because it is one of only a few regulatory land use programs in the country that involve a cooperative implementation effort between State and local governments. The purpose of this arrangement is to provide local governments with the flexibility needed to address the unique physical, economic, and social characteristics of the particular jurisdiction while ensuring that the goals, purposes, policies, and criteria of Maryland’s Critical Area Program are implemented in a consistent and uniform manner throughout the State.

Each jurisdiction with its own planning and zoning authority adopted its own local Critical Area program based on the Criteria promulgated by the Commission. The Critical Area Law recognized the primary responsibility of local governments for land use decisions. By implementing the Law in this fashion, local governments were allowed to add to or modify existing zoning and land use regulations, providing the flexibility necessary to accommodate local conditions. As a result, most jurisdictions’ Critical Area Programs differ substantially from one another.

Each local government was required to develop and submit a program to the Commission by March 1987; and these local programs were to be reviewed, amended, and approved by the Commission by June 1988. The deadline for submittal to the Commission was extended but many jurisdictions did not meet the deadline Ultimately, after many months of intense effort by the Critical Area Commission and local governments, all jurisdictions that were required to have a local program, had one in place by 1990.

The Critical Area Law requires local governments to review their Critical Area programs comprehensively every six years. These reviews are necessary for the Commission to make sure that local programs are kept up to date and that required legislation is incorporated into local codes and ordinances. The reviews also provide an opportunity for local governments to work closely with the Commission to modify provisions of their programs to accommodate new State or local plans or initiatives and to address any specific implementation challenges that they are facing. In addition to changes that are regularly made to local plans and ordinances, many jurisdictions are in the process of revising their Critical Area Maps and converting them to an electronic format. This enables local governments to make use of state-of-the-art technology and provides opportunities to make these resources more accessible to the public.

In general, for all development activities on private lands or lands owned by a local government, the local planning and zoning department is the primary agency responsible for reviewing and approving building permits, site plans, and subdivision plans. Private landowners do not have to apply to the Critical Area Commission for approval of development plans or building permits. The Commission does perform an oversight role with respect to local review of projects. Comments and recommendations on such projects are provided to the local government by the Commission in order to aid the local government in the decision-making process.

The Commission also does not function as an independent enforcement authority and does not have its own inspectors. Instead, the Commission works cooperatively with local enforcement officials to assist them in effectively administering and implementing their local Critical Area regulations. In 2004, the Critical Area Law was amended to allow local governments to request assistance from the Office of the Attorney General through the Critical Area Commission to provide assistance in pursuing and remediating serious violations.

The provisions of Maryland’s Critical Area Program are intended to provide general information about the basic requirements and standards included in the Critical Area Law and Criteria. However, it should be noted that each local government has its own locally implemented program, and this guide is not a substitute for local ordinances, codes, regulations, and policies that may be more specific and detailed.